A beautiful life cut short

April 26, 2018 • Uncategorized

College of Public Health & Texas Center for Health Disparities

Community Blog

In late October of 2005, I gave a presentation on high- risk domestic violence to law enforcement officers in Dallas. I had spent the prior 14 years addressing domestic violence as a social worker and a researcher, and had totally immersed myself in trying to better understand and intervene before violent relationships become lethal. The evening after that presentation, I had a first date with Paul, who later became my husband. When Paul asked a polite question about my workday, I talked about my presentation at the police department. His response changed the tone of our casual conversation.

“That’s interesting,” he said. “I have some personal experience with that.”

That moment marked the point when domestic violence crossed from being my area of research and practice- to intruding into my personal life.

In 1984, Paul’s life was tragically altered when his older sister was murdered by her husband. Maria Guadalupe, fondly called Ñeca (short for muñeca, or “doll” in Spanish), had separated from her husband two years earlier, but did not have the resources to get a divorce. Like many abusive spouses, Ñeca’s husband David sought to isolate her from her family, and convinced her to move from Texas to California when they were newly married. After several years, Ñeca could no longer tolerate the abuse, but had grown accustomed to the California coast. She found an apartment and was determined to make it on her own. David, too, showed signs of letting go as he moved in with another woman. However, as she became more independent, David began to realize he could no longer control her. He stalked her, broke into her apartment, and engaged in an array of threatening behaviors that we now recognize as lethality indicators. In 1984, however, there were no stalking laws, no victim advocacy programs, and little recognition that David was dangerous.

In 1984, Paul’s life was tragically altered when his older sister was murdered by her husband. Maria Guadalupe, fondly called Ñeca (short for muñeca, or “doll” in Spanish), had separated from her husband two years earlier, but did not have the resources to get a divorce. Like many abusive spouses, Ñeca’s husband David sought to isolate her from her family, and convinced her to move from Texas to California when they were newly married. After several years, Ñeca could no longer tolerate the abuse, but had grown accustomed to the California coast. She found an apartment and was determined to make it on her own. David, too, showed signs of letting go as he moved in with another woman. However, as she became more independent, David began to realize he could no longer control her. He stalked her, broke into her apartment, and engaged in an array of threatening behaviors that we now recognize as lethality indicators. In 1984, however, there were no stalking laws, no victim advocacy programs, and little recognition that David was dangerous.

Ñeca’s outlook in the early fall of 1984 was hopeful and positive. She had been promoted at her job and could now afford to get divorced and seek a new healthy relationship. On September 30, after dining with a male colleague from work, she walked into the restaurant parking lot and found David with a knife. He stabbed her in the heart and the back, killing her, and stabbed her dining companion in his hand.

David is serving a life sentence in the San Quentin prison. Every few years he requests a parole hearing from the California Department of Corrections. Paul and his brother Arnold, the youngest of 10 siblings, attend all of these hearings because Ñeca was like a second mother to them. Despite the passage of more than 3 decades, David continues to show hostility and resentment towards Ñeca. Without remorse, he simply discusses his pen-pal relationships with more than 4 dozen women and his hopes of being able to get out of prison and date them someday.

What has changed in three decades is our knowledge and awareness of domestic violence. Today we would recognize David’s instances of strangulation, stalking, threats and sexual assault as signs of danger. In fact, California was the first state in the country to pass anti-stalking legislation and all other states have since followed suit.

Every April, we are invited to participate in the Monterey County District Attorney’s Victims’ Dedication Ceremony. As part of the ceremony, they place red wooden cut-outs of women and children who have been murdered in domestic violence circumstances. One of these women bears the name of Maria Guadalupe Almaguer. This year, we received another invitation- to a parole hearing that will be held in June. The Almaguer family will once again travel to San Quentin and re-live their traumatic loss in the presence of their sister’s murderer.

In the early years of my marriage, I took a break from studying domestic violence. It was frankly hard to see the pain it caused Paul when I spoke about my research. However, as time has passed we both agree that the best way to honor Ñeca’s memory is to bring awareness to the tragedies and traumas of intimate partner violence.

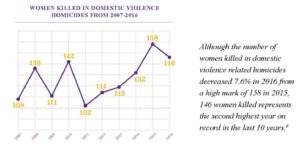

There is still much work to do– the rates of domestic violence homicides in Texas between 2015 and 2016 are the highest they’ve been in 10 years. Tarrant County has a network of organizations and programs that work tirelessly to promote victims’ safety and wellbeing- these include, but are not limited to SafeHaven shelters, One Safe Place Family Justice Center, Women’s Center, JPS Injury and Violence prevention, criminal justice-based advocates, and our own TESSA project that establishes a linkage between primary care clinics and violence services.

This April, as we honor the memory of family violence homicide victims, let’s all consider the ways we can act as individuals and organizations to prevent future violence. Whether that involves offering help, asking the right questions, or dedicating resources to ensure everyone has a chance to feel safe at home; collective action can make a difference.

This April, as we honor the memory of family violence homicide victims, let’s all consider the ways we can act as individuals and organizations to prevent future violence. Whether that involves offering help, asking the right questions, or dedicating resources to ensure everyone has a chance to feel safe at home; collective action can make a difference.

Author:

Emily Spence-Almaguer, PhD, MSW

Associate Dean for Community Engagement and Health Equity

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD006882. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Social media