Home for the Holidays: Reflections on Social Connectedness

December 16, 2017 • Uncategorized

College of Public Health & Texas Center for Health Disparities

Community Blog

I was in my early 20’s when I held my first “real” job as a social worker, serving as a counselor for a domestic violence shelter. In my first year there, I was scheduled to work on Christmas day and I recall how I dreaded the arrival of Christmas morning. I had driven across the state of Florida on Christmas eve, leaving my family behind, and felt strange all alone in the apartment that I shared with roommates. I woke up early on Christmas day, and headed to work feeling sad that I was missing out on something back home. My expectation of what I thought I “should” be doing on Christmas didn’t match up with my reality.

Within an hour of getting to work, I got a call from a woman fleeing her violent husband with her six children in tow. A short time later, they arrived at the shelter—a tired mom and her six adorable children under the age of 8.

My pity party was over. If anything, I felt ashamed that I had been feeling down about having to work on a holiday. This beautiful family, despite the upheaval in their lives, was beginning to unfold and relax in front of me. They had arrived to a safe place, and the kids played freely in the shelter. Along with the other families, they enjoyed the abundant donations of pie, cookies and other goodies in the old shelter kitchen.

Everyone there made the best of that day, despite their circumstances, and that memory has stuck with me.

Nearly two decades later I was contracted to serve as evaluator for the City of Fort Worth’s Directions Home initiative, designed to make homelessness rare, short-term and non-recurring in 10 years. As part of our evaluation, we pulled together an advisory group of men and women who had just been housed through the Directions Home programs. Right before the holidays, I made them my family’s favorite meal for lunch, and the group swapped hopes and dreams for the future. They also shared their new “top shelf” problems—like losing track of their apartment keys and forgetting to charge their cellular phones.

When January arrived we learned that some of the Directions Home residents had really struggled over the holidays. Most lived alone in their “new” apartments, and many found themselves isolated and depressed. Some returned to addictions they thought they had conquered. Some were hospitalized. Despite the profound gratitude they had for ending their homelessness, the shock of being so alone over the holidays was overwhelming.

Being “home for the holidays” holds so many meanings. We

hope for joyful family gatherings. Delicious home cooked food.

Giving gifts to our family and friends. Reflecting on a year gone by.

______________________________________________________

What happens when our visions of happy holidays don’t match up to the realities of our lives? For those struggling with homelessness, violence, poverty, depression, grief, or addictions- do the pressures of the holiday season make things worse?

In Tarrant County, a substantial proportion of the community is struggling. The 2016 county health rankings show that odds are good many people in our community will not have a holiday season that aligns with their expectations.

The Health of Tarrant County

During the 2017 Tarrant County Homeless Coalition point-in-time assessment, there were nearly 1,924 people homeless on January 26th(TCHC, 2017). Almost 200 families had no place to call home and 390 people were identified as sleeping outside or other locations not meant for human habitation. Last year, Safe Haven provided emergency shelter to 1698 women and children fleeing violence in their homes (SafeHaven, 2016).

Thinking back to my memories of domestic violence shelter work and evaluating Directions Home–what do these two memories have in common?

They demonstrate the power of social connectedness.

One family was able to at least partially salvage a Christmas morning that began horrifically, while others went from appreciating the new “abundance” in their lives to realizing that they were more isolated than ever before.

A large body of research characterizes social connectedness as a biological human need necessary for survival. Social relationships act as a protective factor to extend life, and the disruption of these relationships increases the risk of death and disease (Holt-Lunstad, 2018). During the holiday season, we are bombarded with media messages and marketing suggesting that spending money will bring us happiness. Yet, reaching out to strengthen our social connections is something that costs us little and brings a greater return on quality of life.

As you navigate the hustle and bustle of the holiday season, consider your social connections. What are you doing to reinforce existing relationships or repair strained ones? Do you know someone with limited social connections to whom you can reach out? Do you come across people who might feel invisible to others? You may not be able to end someone’s homelessness, but reaching out in a way that says, “I see you and I care about your life” can be impactful.

Should you also be in a position to make a financial contribution near the end of this 2017 tax year, please consider donating to our community partners who work tirelessly to improve the lives of individuals and families struggling with housing, poverty, mental health, addictions, violence, food insecurity, isolation and other barriers to living long, healthy and happy lives.

Author: Emily Spence-Almaguer, MSW, PhD. Dr. Spence-Almaguer is Associate Dean for Community Engagement and Health Equity for the College of Public Health.

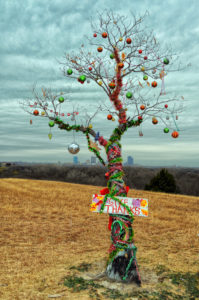

Our “click-through” photo was taken by Ronnie Wiggen and is an image of Fort Worth’s “Homeless Christmas Tree”. For more information, read this story about what this tree means to our community.

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2018). Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annual Review of Psychology, 69: 21.1-21.22 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD006882. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Social media