Losing Texas Mothers: Maternal Mortality in the Lone Star State

May 10, 2018 • Uncategorized

College of Public Health & Texas Center for Health Disparities

Community Blog

– Hope Edelman, Motherless Daughters: The Legacy of Loss – Sidney Taylor

The Texas Tribune follows the issue of Maternal Mortality in Texas featuring such stories as Michelle Zavala who died 9 days after giving birth to her daughter, Clara, from a blood clot in her heart caused by her pregnancy…she was just 35 years old. Pictures at her funeral showed the life of a vibrant woman cut short. In one, she smiled with her newborn daughter, Clara, nestled under her chin, another kissing her husband, Chris, on vacation. Other photos radiated the positivity for which she was loved (Evans, 2018).

Through the years, the publication has shared harrowing tales of mothers enduring medical nightmares, hemorrhaging (or bleeding out) after delivery, losing babies during delivery and suffering strokes and heart attacks (Evans, 2018). Sable Swallow, 25 years old, could hear her brain bleeding in the Walgreens parking lot as she waited in the car for her husband to pick up prescriptions with her newborn son…she was having a stroke. She said she could literally, “Feel my heart beating into my head.” Swallow had high blood pressure after giving birth, a condition known as postpartum eclampsia. Despite reporting repeatedly, she had a terrible headache, she was discharged from the hospital. She survived but endured a long, financially devastating road to recovery. In fact, maternal morbidity (severe problems without death) occurs at a rate of 50:1 when compared to mortality (TDSHS, 2014).

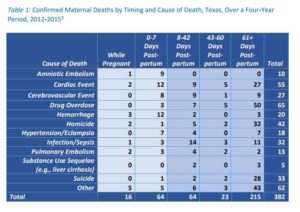

Maternal Morbidity and Mortality is a global public health issue with local urgency. In 2015, the U.S. maternal death rate was 26.4 per 100,000 per live birth (GBD, 2015). This rate is more than double the 1987 U.S. rate of 7.2 deaths per 100,000 births (CDC, 2016). In 2016, Texas was reported to exceed the maternal death rate for the entire developed world at 35.8 per 100,000 live births (MacDorman et al., 2016). However, a new study published in 2018 examined the rate differently lowering the Texas rate to 14.6 per 100,000 live births; although, still unacceptable and disparities exist (Baeva et al., 2018).

Experts and advocates say maternal deaths are a symptom of the bigger problem…too many Texas women, particularly low-income, rural and African American women, don’t have access to health insurance, birth control, mental health care, substance abuse treatment and other services that could help them become healthier before and after pregnancy. Even if they have access, Roman et al. (2017) found that African American new moms 1) had difficulty understanding and communicating with their providers; and 2) felt instructions did not translate to their community setting. Although nurses provide education to all women who give birth, common potential problems may not be presented in a usable way. A woman’s ability to use discharge instructions may depend on the large volume given, culture, degree of sleep deprivation, physical and emotional changes, possible side effects of medicines, and low health literacy (Chugh et al., 2009; Roman et al., 2017). Women may not understand if symptoms after birth are normal or abnormal and thus, should go to the doctor or hospital (Suplee et al., 2017).

What can be done? Overall, Texas and the Texas healthcare systems should allocate dollars that invest in women’s health ensuring high quality health care before, during and following pregnancy. This includes enabling healthy living before and after pregnancy, improving access to care and ensuring readiness and response to obstetric emergencies. At the same time, improved education after birth could improve women’s ability to recognize and respond to problems preventing worsening problems and death. Different people in different settings will use the information based on what they know. Improving postnatal instruction will help new mothers understand possible problems given their context and possibly reduce maternal morbidity and death.

What can be done? Overall, Texas and the Texas healthcare systems should allocate dollars that invest in women’s health ensuring high quality health care before, during and following pregnancy. This includes enabling healthy living before and after pregnancy, improving access to care and ensuring readiness and response to obstetric emergencies. At the same time, improved education after birth could improve women’s ability to recognize and respond to problems preventing worsening problems and death. Different people in different settings will use the information based on what they know. Improving postnatal instruction will help new mothers understand possible problems given their context and possibly reduce maternal morbidity and death.

At UNTHSC College of Public Health, we offer a Maternal Child Health MPH degree that focuses on resolving these issues and improving maternal child health across the globe. The UNT Health Science Center also provides support to the Texas Maternal Morbidity and Mortality Task Force by preparing all maternal death medical records for review by Task Force members to assist in determining solutions to this urgent matter.

We Love Our Mothers…in May we recognize Mother’s Day, the second most popular holiday for gift-giving, following Christmas. Let’s make sure they are around to celebrate.

Authors

Amy Raines-Milenkov, DrPH

Teresa Wagner, DrPH, MS, CPH, RD/LD

Baeva, S., Saxton, D., Ruggiero, K., Kormondy, M., Hollier, L., Hellerstedt, J., Hall, M., & Archer, N. (2018). Identifying Maternal Deaths in Texas Using an Enhanced Method, 2012. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(5), 762-769.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html

Chugh, A., Williams, M.V., Grigsby, J., & Coleman, E.A. (2009). Better transitions: improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Frontiers in Health Services Management, 25, 11-32.

Evans, M. (2018). Dangerous Deliveries. The Texas Tribune. Retrieved from https://apps.texastribune.org/dangerous-deliveries/

GBD Maternal Mortality Collaborators. (2015). Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Retrieved from http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(16)31470-2.pdf

MacDorman, M.F., Declercq, E., Cabral, H. & Morton, C. (2016). Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: Disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 128(3), 447-55.

Roman, L. A., et al. (2017). Understanding Perspectives of African American Medicaid-Insured Women on the Process of Perinatal Care: An Opportunity for Systems Improvement. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21, 81-92.

Suplee P.D., Bingham D., & Kleppel L (2017). Nurses’ knowledge and teaching of possible postpartum complications. The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 42.

Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS). (2014). Hospital Inpatient Discharge Public Use Data File. Office of Program Decision Support.

Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS). (2017). Legislative Brief: Investigating Maternal Mortality in Texas. Maternal & Child Health Epidemiology, Division for Community Health Improvement. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files//documents/about‐hhs/communications‐events/meetings‐events/maternalmortality‐morbidity/m3tf‐agenda7‐170929.pdf

Umlauf Scpulture Garden & Museum. “Mother and Child” 1972, Bronze Charles, Umlaufe

http://www.umlaufsculpture.org/1970‐1985

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD006882. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Social media