Medicine: Are you taking what you think you’re taking?

December 10, 2018 • Uncategorized

College of Public Health & Texas Center for Health Disparities Community Blog

The Problem

Every day, millions of people across the globe do not take their medications correctly. They might be taking too much or too little. The results can have bad consequences. These might be accidental overdose, poor control of chronic disease or death.

Recently, my coworker told me a story about his dad. His dad keeps his gabapentin, a medication used for treating pain, in the refrigerator. In the past two days, he hasn’t been sleeping well because his hip pain has been keeping him up at night. It was later discovered, he had been taking acidophilus instead, an over the counter probiotic. He also keeps acidophilus in his refrigerator. As a result, he started taking more of his pain medication “to make up for it”.

His hip hurts because he had fallen recently, and it had to be surgically repaired. Taking too much of his pain medication can make him drowsy putting him at risk of falling again. This cycle of increased risks from improper medication use can be seen in the stories of different people’s lives every day.

What can be done?

Medication reconciliation is the process of “comparing a patient’s current medication regimen against a physician’s admission, transfer, or discharge orders to identify discrepancies (any problems)” (MATCH, 2012). During healthcare appointments, patients are usually asked what medications they take and how they take each. This patient list is compared to the current list on file with the doctor to create a single medication list as the “one source of truth”. Unfortunately, the list of what the patient should take at home isn’t always easily communicated by providers or readily understood by patients.

Better Communication

Taking the time to check provider communication success along with the patient’s understanding of their medications may save time and money in the long run. Correcting misunderstanding can prevent adverse events that lead to unnecessary hospitalizations, emergency room visits and added health care appointments. Low Health Literacy contributes significantly to adverse events and the increased cost of care (Weiss, 2007). Poor outcomes from problems understanding how to use medication have led this topic to receive national attention.

Health literacy is more than just reading and writing. The Institute of Medicine (2004) defines health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”

Problems understanding medication are a health literacy concern. Lack of good communication may not only cause adverse events but may also limit ability to achieve medication adherence (taking medication as prescribed for general health maintenance). Current strategies for safe medication use have not been effective. These strategies not only fail for the general public but especially people with limited health literacy.

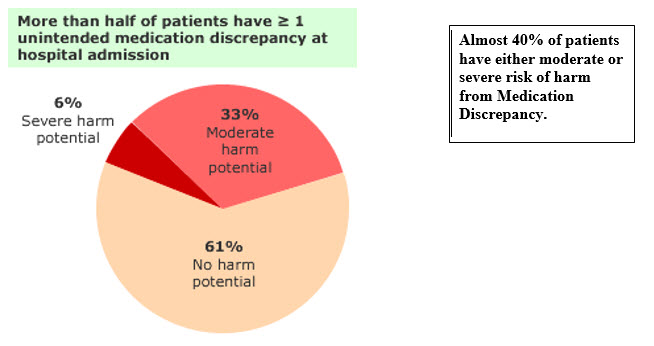

Although, more than half of patients have greater or equal to one unintended medication discrepancy (taking a wrong medicine, taking more than one of the same type or not taking a prescribed medicine) at hospital admission, 61% have no harm potential (risk of an adverse event) but almost 40% of patients have either moderate or severe risk of harm (Figure 1).

Health Literate Care

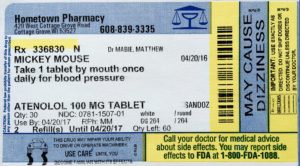

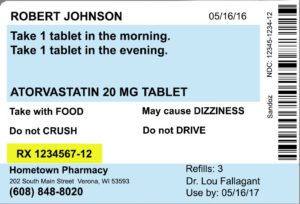

All health professionals should embrace the problem of limited health literacy to improve health outcomes. This can help people get healthy and stay healthy. For medication adherence, providers from all professions need to implement strategies for clear communication in order to improve medication management. For example, new health literate labels are one solution to improving understanding and usability of medication information.

Additionally, Pharmacists specialize in Medication Therapy Management (Figure 2) and can review your medication list. They reconcile medications to help ensure that people are taking them correctly. These services help you create and maintain a good, correct medication list. It is important to have good understanding of an up-to-date medication list and have a caregiver or significant other also understand that list. Remember to bring your medications or at least your list each time you go to the hospital, emergency room, or doctor’s office. This helps ensure that the providers caring for you have the most accurate and up-to-date information when making decisions about your care. This leads to SaferCare!

Authors

Marian Gaviola, PharmD, BCCCP, Assistant Professor of Pharmacotherapy, UNT System College of Pharmacy, Fellow, Steps Toward Academic Research (STAR) Leadership Program

Teresa Wagner, DrPH, MS, CPH, RD/LD, CHWI, Assistant Professor, UNT Health Science Center, College of Public Health, Senior Fellow, SaferCare Texas, Fellow, Steps Toward Academic Research (STAR) Leadership Program

References

Cornish, P., Knowles, S., Marchesano, R. et al. (2005). Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165, 424-429.

Graham, S., & Brookey, J. (2008). Do Patients Understand? The Permanente Journal, 12(3), 67–69. Retrieved from https://www.pharmacist.com/medication-therapy-management-services

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2004). Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, D.C.: The Institute of Medicine & The National Academies Press.

Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) Toolkit for Medication Reconciliation. Content last reviewed August 2012. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/patient-safety-resources/resources/match/index.html

Weiss, B.D. (2007). Health literacy: can your patients understand you? 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association and AMA Foundation.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD006882. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Social media