HSC Researcher found deaths that involved heroin or fentanyl skyrocketed

As the nation finds itself in the grips of an ongoing deadly fentanyl crisis, a recent study involving a researcher at The University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth has revealed an equally staggering drug-related threat to public health.

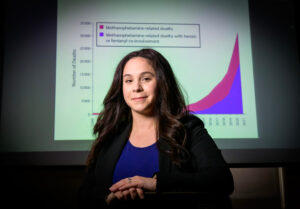

Dr. Andrew Yockey, an assistant professor of biostatistics and epidemiology in HSC’s School of Public Health — along with co-author author Dr. Rachel Hoopsick from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign — found methamphetamine-related mortality increased 50-fold from 1999 to 2021. The proportion of those deaths that involved heroin or fentanyl also skyrocketed, rising as high as 61.2% in 2021.

For the study, the researchers reviewed data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“I was really surprised to see the drastic increase in mortality rates,” Yockey said, “I knew meth use had increased, but the mortality rates left my jaw dropped.

“Our work serves as a stepping stone for harm reduction efforts, particularly among local and rural populations. I am from Ohio, and methamphetamine use there is rampant. I’ve had so many friends overdose because of methamphetamine, so this work serves as a beginning plan to reduce mortality rates and increase behavioral health/education initiatives.”

The growing problem of methamphetamine deaths

Based on preliminary data from the CDC, deaths involving synthetic opioids — largely fentanyl — rose to 71,000 from 58,000 over a 12-month period ending in Feb. of this year, while those associated with stimulants like methamphetamine, which has grown cheaper and more lethal in recent years, increased to 33,000 from 25,000. Over that same time, there were more than 1,334 fentanyl-related deaths in Texas.

Because fentanyl is a white powder, it can be easily mixed with other drugs, including opioids like heroin, and stimulants like meth. Such mixtures can prove lethal if drug users are unaware they are taking fentanyl or are unsure of the dose.

“This study confirms that we need to do more and better to address harm reduction by closing the know-do gap,” said Shafik Dharamsi, dean of HSC’s School of Public Health. “Research findings that don’t result in changes in policy and practice fail to improve quality and conditions of life, particularly in our most vulnerable populations. We need greater investment in implementation efforts and partnerships with local communities to develop and implement solutions to public health problems.”

Harm reduction approach to dealing with methamphetamine-related deaths

Hoopsick, who is the study’s primary author, said this project arose out of a community syringe exchange program she worked on in conjunction with the Champaign-Urbana Public Health District. She and others surveyed people in that community who inject drugs to gauge their harm reduction needs.

“I expected these folks to primarily be using opioids but was surprised to find that many reported injecting methamphetamine — often with heroin or fentanyl,” she said. “This got me thinking that perhaps the increases we’ve seen in methamphetamine mortality may be driven by co-use of these substances.”

President Joe Biden is the first president to embrace harm reduction, an approach that has been criticized by some as enabling drug users but praised by addiction experts as a way to keep drug users alive while providing access to treatment and support.

Instead of pushing abstinence, the approach aims to lower the risk of a user dying or acquiring infectious diseases by offering sterile equipment — through syringe exchanges, for example — or tools to check drugs for the presence of fentanyl. Strips that can detect fentanyl have become increasingly valuable resources for local health officials, though the strips aren’t yet legal in every state.

Recent settlements with prescription opioid manufacturers and distributors will soon bring new resources to states battling the overdose epidemic.

“We need more robust harm reduction services (meeting people where they are, but not leaving them there) – particularly for people who co-use stimulants and opioids,” Hoopsick said. “Abstinence-based approaches don’t work in sex education, and they certainly don’t work when it comes to reducing drug-related harms.

“There is a tremendous amount of evidence supporting the efficacy of harm reduction services to reduce substance-related morbidity and mortality but there is a lack of political will in the U.S. to make these services legal and accessible everywhere.”

Social media