A breakthrough for those with PKU

By Jan Jarvis

As a child Erin Gisler’s diet was limited to fruits and vegetables. No dairy products, meat, fish, chicken, eggs beans or nuts.

Gisler was an infant when she was diagnosed with phenylketonuria or PKU, a genetic disorder that causes the amino acid phenylalanine to build up in the body. When a person with PKU eats foods that are high in protein it can lead to serious health problems. The only treatment is a lifelong restricted diet.

“I was always hungry because there were just not enough foods I could eat,” Gisler said.

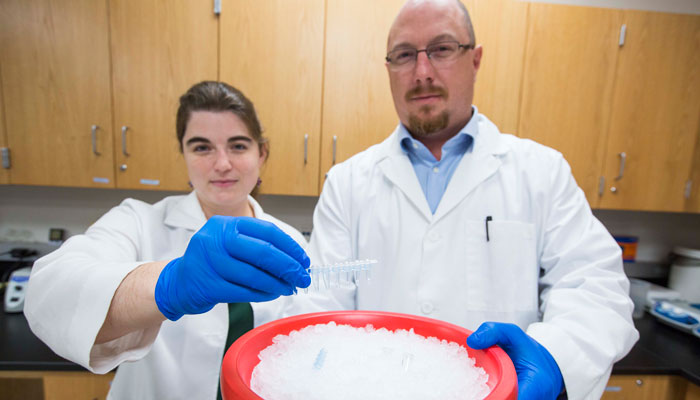

For Gisler and others with PKU, a genetically engineered probiotic developed by UNT Health Science Center researchers Michael Allen, PhD and Katherine Durrer, PhD, holds promise as a potential new treatment. Their research was published May 17 in the journal PLOS ONE.

“We have developed a probiotic bacterium that is genetically engineered to break down phenylanine in the gut before it is absorbed into the blood,” said Dr. Allen, Associate Professor, Institute for Molecular Medicine. “This would allow people with PKU to live more normal lives.”

The genetically engineered probiotic is the first to be patented and published, Allen said.

“People with PKU can live a normal life span,” said Dr. Durrer, Research Associate, Institute for Molecular Medicine. “But if they live with PKU, they have to adhere to the dietary restrictions.”

A 9-year-old with PKU is only able to eat approximately 8 grams of protein a day in the form of naturally occurring foods, Durrer said. That’s the equivalent of a single serving of lunch meat or two tablespoons of peanut butter.

The demands of the diet force parents to go to extremes to make sure their children eat the right foods.

“On some days that would mean choosing between three-and-a-half grapes and two cherry tomatoes with their lunch in order to have other treats later,” Dr. Durrer said. “Parents do things like pin signs to their kids’ shirts saying ‘Do not feed me’ for the first few days of school.”

Gisler said the diet was difficult to follow when she was a teenager and wanted to eat pizza and hamburgers like her friends did. She said she had trouble concentrating and struggled with moodiness and memory problems. The health problems still affect her today.

But the consequences of straying from the diet are severe. If individuals with PKU don’t reduce their protein intake, the amount of phenylalanine in the blood skyrockets. Although not instantaneous, this increase in blood phenylalanine can lead to seizures, neuropathy, intellectual disabilities and other neurological problems, Dr. Allen said.

To prevent neurological problems caused by PKU, infants are tested at birth and the diet usually starts within the first seven to 10 days of life. In the U.S. about one in 10,000 to 15,000 babies are born with PKU each year.

While the only treatment is a protein-restricted diet, supplements and food substitutes have been used, Dr. Allen said. Formulas and a prescription medication are available but often are costly or unlikely to be covered by insurance.

Gisler said she looks forward to other treatment options.

“A new treatment could make a huge difference to people with PKU,” Gisler said. “Anything that helps lower blood phenylalanine levels would be awesome. Following the diet is very demanding, and it puts a lot of stress on you.”

Social media