A bloody mystery of Bonnie and Clyde

By Jeff Carlton

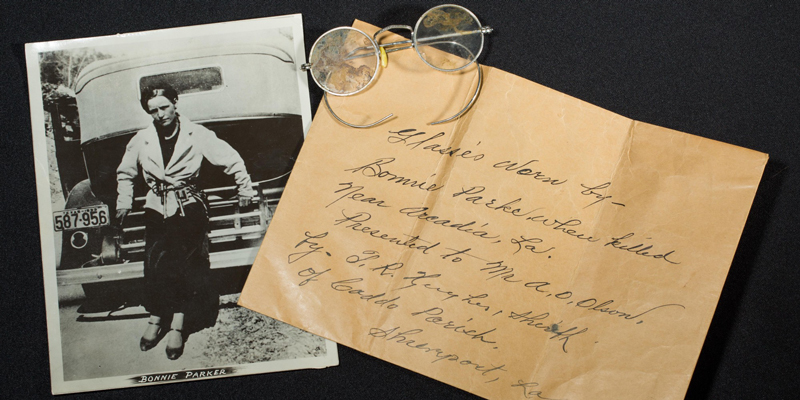

She wore eyeglasses — the kind one wears to see better, not dark ones for glare or disguise. They were silver rimmed, and fell from her shot-torn face as her limp form was lowered from the car onto a funeral truck. The glasses were thickly splotched with blood, the blood of a killer’s girl friend, whose thorny trek through a short-lived life, haunted by man-hunting officers, was lastly and effectively pricked with the carrying out of orders to “shoot to kill.”

— Shreveport Journal, May 24, 1934

Eighty-three years before a pair of blood-splattered spectacles came to a DNA testing lab at UNT Health Science Center, they allegedly fell from the face of infamous gangster Bonnie Parker after she was shot dead on a rural Louisiana road. FBI archives describe Parker as a “part-time waitress and amateur poet from a poor Dallas home who was bored with life.” She was one-half of the notorious Bonnie and Clyde duo that eluded law enforcement officials across the region.

The pair was responsible for at least a dozen murders, with most believing that Clyde Barrow was the triggerman and Parker his willing accomplice. Law enforcement officials, led by Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, killed the couple in a roadside ambush on May 23, 1934. Parker was shot dozens of times.

Now the glasses she purportedly wore in her final days were in a Health Science Center laboratory. The quirky economics of the collectibles industry had brought them here. The glasses were up for auction, and they would be worth a lot more if DNA testing proved that the dried red smudges on the lens were from Parker’s blood.

It was an especially tricky assignment, even for the UNT Center for Human Identification, recognized as one of the nation’s top DNA laboratories. Since 2003, the lab has processed more than 5,200 human remains and made more than 1,700 DNA associations that led to identifications. In addition, the Center has analyzed more than 14,400 family reference samples, representing more than 8,000 missing person cases.

Among the factors that complicated this case: the age of the artifact, exposure to the elements and the likelihood that it was handled by a number of different people.

“There are a number of unique challenges in testing dried blood that is nearly 85 years old,” said Bruce Budowle, PhD, Co-Director of the Center for Human Identification.

And even if DNA experts could obtain a clean sample, they would still need to compare it to the DNA of a blood relative of Parker. But where would they find one?

Bonnie and Clyde descendants

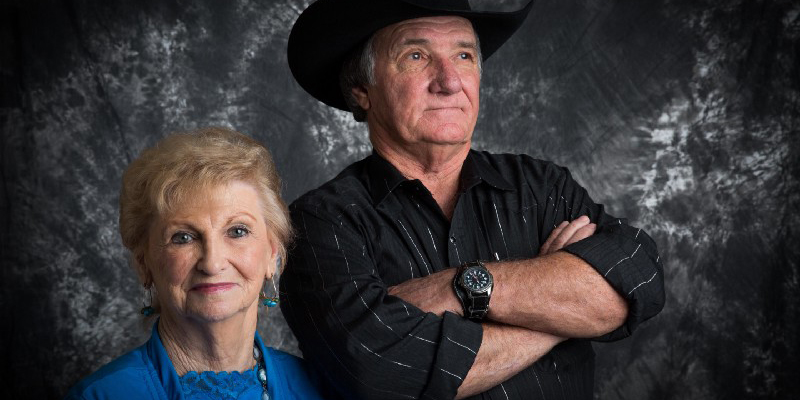

It was as unlikely a pair as has ever pulled into a parking lot at UNT Health Science Center. Behind the wheel of a white Ford F150 pickup was the nephew of Clyde Barrow. Riding shotgun was the niece of Bonnie Parker.

“I’m her chauffeur and her bodyguard,” joked Buddy Barrow, 70.

Being Clyde Barrow’s nephew is a role Buddy relishes. He was dressed in all black — from the Stetson on his head to the silver-studded belt around his waist to the Tony Lama snakeskin boots on his feet. “Every time a snake sheds its skin, I get a new pair of boots,” he explained.

He is bemused by the interest in Bonnie and Clyde memorabilia, a phenomenon he’s dealt with for decades. At his home in Sunnyvale, near Dallas, he says he has a trunk full of family heirlooms connected to the gangster. He insists none of it will be sold, so long as he’s alive.

“My wife says, ‘I’ll just wait ’til you’re dead, then,’” he said.

More resigned than amused is Rhea Leen Linder, 83, whose original name was Bonnie Rhea Parker, after her aunt. But that burden was too heavy for a child, especially so soon after her namesake’s role in such terrible crimes. She started going by Rhea Leen in grade school.

“We hid from it. It was not discussed at all,” Linder said. “Kids used to tell me, ‘I’m not allowed to play with you.’”

But Linder doesn’t hide from it anymore. A retired secretary who lives in Garland, Linder says living into her 80s has given her the freedom to speak her mind, even about touchy subjects such as her long-ago divorce.

“Us Parker women don’t make good choices in men, I guess,” she said. “Bonnie said, ‘Life ain’t worth living without Clyde.’ But that doesn’t run in the family. Loyal until death? No thanks.”

Linder chatted away as a forensic geneticist swabbed her mouth to obtain a DNA sample, which could be used as a comparison to the apparent blood that caked the old spectacles.

Bonnie Parker aligned herself with a cop killer and bank robber, Linder said. Yet eight decades and one famous Hollywood depiction later, their exploits have seemingly been sanitized and romanticized.

“I resent Bonnie and Clyde for what they put their families through — and they came from good families,” Linder said. “They were outlaws, no matter if they were in love. They still did bad.”

Testing the specs

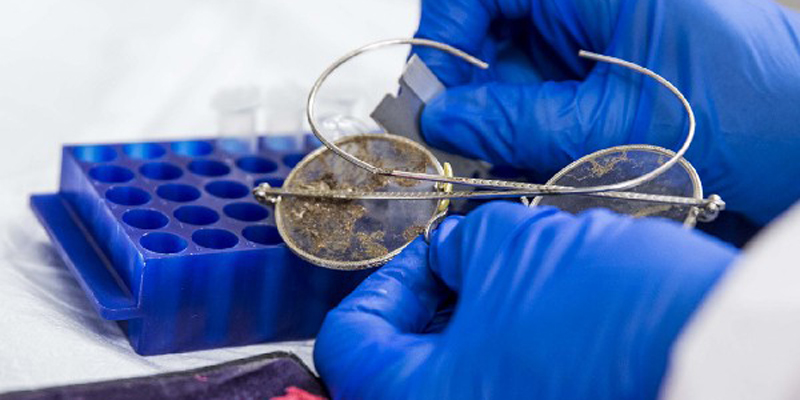

Despite the remarkable nature of the artifact being tested, it was just another day at the laboratory for Angie Ambers, PhD, a forensic geneticist with the UNT Center for Human Identification.

Dr. Ambers specializes in historical and archaeological cases. One case involved exhuming a guerrilla scout from the Civil War to see if he had fathered a child with his American Indian maid. She recently was in Deadwood, S.D., after a homeowner building a retaining wall had discovered the remains of a19th centurysettler in the pioneer town.

Her favorite current case involves two adult male skeletons pulled from the shipwreck of the La Belle, a ship under the command of the French explorer La Salle that sank off the Texas coast in 1686. The wreck was discovered in 1995. Dr. Ambers is using the latest DNA techniques and working with a French genealogist to see if they can identify the skeletons.

The Bonnie Parker spectacles were especially intriguing. Their authenticity is clear, said Bobby Livingston, Executive Vice President of RR Auction in Massachusetts.

The sheriff of Caddo Parish, La., recovered them from the ambush and kept them as a bloody keepsake until 1938, when he sent them as a gift to an Oklahoma oilman. The oilman’s family returned the spectacles to the sheriff’s family in 1976, according to the paper trail.

In 1996, they were sold to a private collector in Massachusetts, who eventually decided to sell them through RR Auction earlier this year as part of a “Gangsters, Outlaws & Lawmen” sale. The auction house estimated the glasses would sell for upward of $50,000.

But for the sake of his auction house’s credibility, Livingston wanted to see if the red stains came from Parker’s blood.

Working in her lab, Dr. Ambers performed DNA extractions on swabbings of both lenses and the rim of the glasses. Preliminary testing, however, revealed two key problems: low DNA quantities that were insufficient to obtain full profiles, and the presence of a small amount of male DNA.

Could it be Barrow’s DNA mixed in? Or could it be skin cells, the result of contamination from other people handling the glasses?

“The age of the glasses is not necessarily the issue here,” Dr. Ambers said. “It’s the fact that so many people have come into contact with the glasses. Deciphering the DNA mixture is what’s so difficult. Another complicating factor is that we don’t have a family reference sample from a closer family member, such as a sibling or mother.”

The inconclusive result prompted Livingston to remove the spectacles from auction. But future testing is possible, he said, depending on the wishes of the owner of the glasses.

If it comes to that, Dr. Ambers will be ready. She pulled a single hair that was caked to the lens and has additional untested samples that could yield clean DNA in sufficient amounts. They are in a freezer at UNTHSC, along with the DNA sample from Linder.

“These are the coldest of the cold cases, and I like a good challenge,” Dr. Ambers said. “I’m a history buff — and this kind of work is about answering questions and solving mysteries.”

Social media