Holocaust survivor

By Betsy Friauf

Andras Lacko is a Holocaust survivor. From a childhood of persecution that would have crushed many, he forged a resilience and a quiet, straightforward brand of leadership. He is, quite simply, a rock of strength and stability for his students, his co-workers and future generations.

As a Jewish grade-school boy in Budapest during World War II, he was hungry, cold, sick, denied an education, crammed into a three-bedroom apartment with 61 others, separated from his parents whose jobs and rights were stripped, placed in an orphanage, bombed from the air and trapped in intense house-to-house fighting. He wasn’t yet 10 years old.

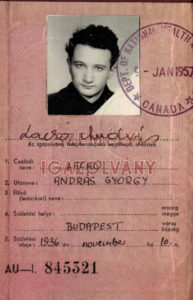

Later, at age 19, when he was an aspiring researcher, the Soviets took over Hungary and forced him into a different vocation. He left his home and family and escaped first to Austria, then Canada with only a briefcase, his high school graduation suit and a passport.

No wonder he can’t be rattled.

Helping students stay optimistic

Today, as a professor in UNTHSC’s Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease, Dr. Lacko, 80, teaches the next generation of physicians and other health professionals. He also researches ways to help more people survive cancer.

“We are finding ways to make anti-cancer drugs work better,” he said. “We’re looking for a better delivery system, essentially a Trojan horse carrying particles that kill cancer cells.”

Observed one former student, “It’s a great experience when you can get even a small glimpse of his thought process.”

“Dr. Lacko was always positive when I hit a roadblock with my pediatric-cancer research project,” said Gaile Vitug, DO, a recent graduate of the Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine and now a pediatric resident at UT Health Science Center at San Antonio.

“He wholeheartedly wanted me to succeed, and he took time to go over solutions,” she said. “I am so grateful that Dr. Lacko took me under his wing and taught me about biochemistry and pediatric cancer.”

Ask Dr. Lacko’s colleagues, students and his grown children to describe him, and you’ll hear the word perseverance. He credits his parents’ character with helping him put first things first and avoiding discouragement during setbacks.

“I grew up in a time and place where we had to be resourceful and resilient to survive,” he said. “After the bombing stopped, we would go out in the rubble to see if we could find anything useful. We were starving, and we begged bread from the soldiers. It’s a lesson in basic survival. Once you do that, you can do anything.”

Says one of his daughters, Annette Baker, “Everything rolls right off of him.”

From tragedy, resilience

In Hungary, where Dr. Lacko was born, the Holocaust started late, but it was the most brutally efficient in all of Europe. Hungary was home to 800,000 Jews when Hitler invaded in 1944. By war’s end in 1945, 600,000 were gone. Dr. Lacko says he and his parents survived by a series of coincidences, “or maybe they were miracles.”

His father was sent away to perform military labor, but not in one of the most brutal brigades. When Lacko was 7, he and his mother were forced from their home into a small section of Budapest where Jews lived in extremely overcrowded poverty.

Eventually, the Nazis pounded on the door and rounded up all the women between ages 18 and 40. Lacko’s mother hid inside a sofa. She escaped detection once but was discovered on a later sweep. She was marched with other Jewish women to a soccer stadium. They waited under heavy guard to be registered and herded into trains that would deport them to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

However, as the day wore on, Mrs. Lacko’s group was yet to be registered. They were sent home with instructions to report the following day.

She knew she had to disappear. Instead of reporting as instructed, she cut the yellow star from her coat and Lacko’s, placed her son in an orphanage and went into hiding.

Lacko was slated to be moved back into the overcrowded ghetto, but another coincidence or miracle intervened. He caught scarlet fever and was well-treated in a hospital for weeks. After recovering, he stumbled across the war-torn city with an older boy. Hitler had ordered German and Hungarian troops to hold off the invading Russians at all costs, a futile effort that cost 38,000 civilian lives. Lacko and his friend hid in a basement during close combat.

When the war ended, the Lacko family reunited, resumed their grocery business and carried on. When Lacko graduated middle school, he was given a chemistry set, “And that was it! That was what I loved.” He had found his calling.

He has been a professor of molecular biology for decades and has served for 41 years on the UNTHSC faculty.

The most important things

Dr. Lacko is a busy man but stays focused on the most important priorities in a world where busy-ness often is confused with effectiveness. He is highly productive, having published more than100 articles, mentored 10 students and advanced education by serving in numerous university and international professional initiatives.

He’s also raised four children, all active in highly responsible corporate, small-business and government professions.

Says his son Peter, an electrical engineer and U.S. Navy veteran: “My father taught me how to play soccer and coached my team for several years. But the thing that I learned from my Dad that means the most to me is that no matter what, you should be there for your children when they need you. I wasn’t the easiest kid to raise. But whenever I needed my Dad, he has been there.”

Dr. Lacko also makes it a priority to help preserve the history of the Holocaust. “I’ve given talks at the Dallas Holocaust Museum. I’ve spoken to junior high and high school students here in Fort Worth, and also to a special-education class.”

He provided testimony of his Holocaust experiences during a 1997 interview conducted by the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation. The foundation has collected the testimony of more than 53,000 Holocaust survivors. Dr. Lacko says of this archive of oral histories, “It should be available to document that the Holocaust happened. There are people who deny it. All the documentation is important as a testimony to what human beings are capable of doing to each other.”

Enduring legacy

Working at an age when many people have been retired for decades, he finds energy and inspiration in the company of young people. “It’s important to educate everyone so they can reach their potential,” he said.

Cheryl Hinze-Schmidt, a recent student who became a research technician, said Dr. Lacko has had a lasting impact on her life.

“His strong will and dedication to every aspect of life, not only work but family, fitness and health – he exercises regularly – continue to be a great role model for me,” she said.

The drive is strong in him to discover new ways to help people be healthy.

“I inherited a lot of curiosity from my mother,” Dr. Lacko said. “Many people are capable and smart. Those who are curious and driven to discovery never lose their drive to solve problems. That is the heart of research. That keeps me going.”

Social media