HSC executive loses brother to opioid addiction

- August 31, 2023

- By: Eric Griffey

- Our People

Related Links

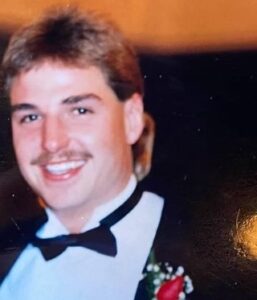

She remembered his boisterous, baritone laugh. She smiled out the corner of her mouth recalling her baby brother’s lush blond hair bouncing atop his head. He was a deep thinker — often burdened by his own world-weary brilliance.

Hans Maack was cerebral, charismatic and tortured. He died in 2020 of a combined overdose of opioids and liver failure at 53 years old.

His sister, Jessica Maack Rangel, executive vice president of health systems for The University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth, still feels the weight of watching her only sibling deteriorate into a snowballing misery of bad choices, bad luck and, most of all, a losing battle with drugs.

“I still have him as one of my emergency contacts,” she said, straightening her posture to stay composed. “Every now and then, when I’m thinking about him in the car, I still call his phone number. There’s no voicemail or anything, but I’m not ready to erase it yet.”

Maack, like so many Americans, became entangled in an all-too-common cycle of addiction, recovery and relapse. His struggle was a life sentence. Born to an addict mother, he began smoking marijuana and drinking alcohol at age 12 after falling in with a fast crowd at a new school in his native Ohio. Eventually, he resorted to stealing his mother’s pills. After having his wisdom teeth removed, he was prescribed his own painkillers and later graduated to a far deadlier class of drug.

The maelstrom of people who have died in the opioid crisis has captivated and horrified a nation. As of 2017, the leading cause of death for Americans under 50 is overdose. The arrival of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids has magnified the perils of addiction. Nearly 110,000 people died last year of drug overdoses in the United States, according to federal data published in May by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Synthetic opioids contributed to about 75,000 of those deaths.

In October, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott announced the launch of the One Pill Kills campaign to combat the growing fentanyl crisis. The state distributed the overdose-reversing drug, Narcan, to 254 counties, including Tarrant. HSC’s SaferCare Texas regularly offers Narcan training classes and helps dispense the potentially life-saving treatment.

Rangel is part of another growing statistic: family members who are left to wonder what else they could have done to help. Loving her brother unconditionally wasn’t enough to save him.

“He told me, ‘Not a day goes by that I just don’t crave it with everything I have,’” she said. “And he also told me, ‘Just know when I’m in the worst part of my addictions, I’m a liar.’ He said, ‘I will do anything to cover up because I don’t want you to be ashamed of me.’”

The struggle for sobriety

She remembered seeing him in a hospital bed — labyrinthine tubes weaved in and out of his body. His stomach was bloated from liver damage and his skin had turned a shade of pale green.

“When I walked into the room, I didn’t even recognize him,” Rangel said.

Maack was in and out of rehab his entire adult life. Rangel said she knew her brother was back on opioids when the two wouldn’t speak for long stretches. Seeing him in that helpless state was the first contact she’d had with him in months.

At the peak of his addiction, Maack used up to 12 opioid pills a day. Though he managed to break away from the pills at several points in his life, he could never give up alcohol.

“I asked him, ‘Do you want to get sober,’” she said. “He said, ‘I don’t know who I am sober. I don’t think I’ve really been sober since I was 12.’ He had some very legitimate fears for which I didn’t have any answers, because that’s just not a world that I understood. He was really afraid.”

The pandemic was particularly devastating for Maack, who owned his own construction company that specialized in restoring historic homes. For most of his adult life, he was functional. He hid his demons well. When the world and his work stopped for a time, Maack found the pull of his addiction became stronger.

“The isolation was very difficult for him — very, very, very difficult,” Rangel said. “Boredom set in. I think for him, such a highly intelligent person, he didn’t have anywhere to put his energy. I suspect that’s where the overdose came from.”

More than 87,000 Americans died of drug overdoses over the 12-month period that ended in September 2021, according to preliminary federal data. That number eclipsed the toll from any year since the opioid epidemic began in the 1990s.

Many treatment programs closed during that time, at least temporarily, and “drop-in centers” that provide support, clean syringes and naloxone cutback services.

When Covid robbed Maack of his ability to make a living, Rangel would send her brother grocery gift cards, hoping he would use them to feed himself. She later learned he spent them on beer. As COVID-19 exacted its toll on the world, Maack eventually stopped reaching out to his sister and returning her calls and texts.

“I really do miss him,” she said. “But I will tell you that the person that he was at the end of his journey was not a very nice person. He just became this very angry person who was nothing like the brother I knew before. His personality changed completely.”

Before long, Rangel was back at his hospital bedside. This time, he wasn’t responding to treatment. She admitted her brother into hospice care and stayed in Ohio for a week to get him settled. The day after she returned home, she got the call that he had passed away.

“I felt great relief,” she said. “It was intense anger mixed with this profound sadness that I was powerless to make a difference. And to some extent, he was so deep in his addiction that he was powerless. He didn’t know anything else because he had been an addict for so long.

“It was really hard because we both saw what our mother did,” she continued. “And for him to choose that same path to me was baffling.”

Removing shame from addiction

She remembered the support groups and community who rallied to her side amid unthinkable grief. She leaned on her faith and memories of who Maack was at his core.

“I think I’m in a pretty healthy place,” Rangel said. “I mean, I have a very strong support system. I have a God that loves me and lots of prayer. It’s a process. At least his story is not completely going in vain. I just want to tell people going through this, ‘Just rid yourself of guilt, because you haven’t done anything to enable intentionally at all.’”

Some experts believe the current opioid epidemic dates back to the ’80s, as several influential journals calmed doctors’ fears about prescribing the drugs. Riding that wave into the mid-1990s, pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed drugs like OxyContin with, at times, fraudulent information. Pill mills dotted the country, and communities were flooded with prescription opioids. By the mid-2000s, those prescriptions evolved into heroin addictions for many during a period when the price of the drug plummeted. Fentanyl arrived in 2014, bringing with it a soaring death toll.

Lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies that peddled in dangerous opioids and intervention programs with eye-popping funding numbers offer some hope to a beleaguered public. As governments at all levels begin to wrap their energy and budgets around the deadliest drug crisis in American history, the human toll continues to unravel families, ruin lives and create untold generational traumas.

For Rangel, her grief and family history with addiction has informed so much of her outlook, whether it be on people, life, her job, faith … everything.

“There’s no judgment, but there is a lot of pain,” she said. “Substance use disorder is so multifaceted — it’s cultural, it’s your upbringing, it’s your coping mechanisms, it’s your genetics.

“I repeatedly said to him, ‘I love you. There is no shame. Let me help you.’ But he didn’t want me to think less of him.”

Social media