The Migala Chronicles

By Alex Branch

Imagine a movie about the Migala brothers, and it looks like scenes from “Indiana Jones,” “Contagion” and “Hacksaw Ridge” spliced together.

Alexandre Migala, DO, a Kung Fu first-degree black belt, hears bullets plinking against his armored car in Sarajevo while treating the wounded during the Bosnian War.

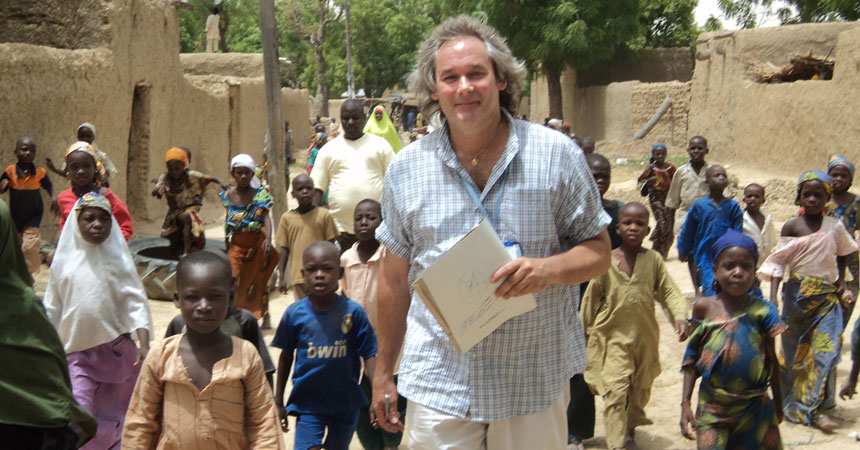

Witold Migala, PhD, MPH, backpack full of vaccines, traipses through remote clay-hut villages in Nigeria, hunting viruses mostly eradicated in the western world.

Henri Migala, EdD, MPH, encounters steely-eyed child soldiers with AK-47s at roadside checkpoints while building a support system for children with AIDS in Uganda.

The three UNT Health Science Center alumni could fill a Hollywood screenwriter’s notebook with their adventures improving third-world public health systems, responding to disasters and conflicts, and helping make the world a safer place.

“No, not many boring stories get told when the family gets together,” Alexandre said.

Alexandre earned his degree from the Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine (TCOM) and has mentored students as a preceptor. Witold and Henri were in the first UNTHSC class to earn master of public health degrees, and both served on committees to create the School of Public Health. Witold went on to be in the first public health PhD cohort to graduate from UNTHSC.

The brothers attribute their sense of service to international experiences during childhood and UNTHSC’s emphasis on helping underserved populations.

“There are a number of great quotes out there about how travel makes one more sympathetic to the human condition,” said Witold, President of the Texas Public Health Association and Adjunct Professor at the UNTHSC School of Public Health. “I think we all realized early on that so many people around the world need help.”

A family resilience

Like any great adventure movie, the story of the Migala brothers would have a prequel. It would be about their parents, Marian and Anne.

Marian was a Polish resistance fighter against the Nazis during World War II. After Germany lost and the Soviets assumed power, he resisted Communist rule until fleeing to Paris.

There, he discovered widespread poverty. But he met Anne, who had aided the resistance movement by hiding and transporting soldiers and Jewish refugees on her family farm.

Marian and Anne married and had three kids — sons Witold and Henri, and a daughter Therese.

Marian learned French and put himself through architecture school. In the 1960s, he immigrated his family to the United States, though he spoke no English.

He learned his third language and got a job designing military bases for the Army and Air Force Exchange Service. Marian and Anne had two more sons — Arthur and Alexandre. Military projects moved the family of seven around the world, from Thailand to Germany, before settling in Texas.

The fearlessness and resilience of Marian and Anne was not lost on their children.

From surgeon to special forces

In an old Nazi tank base near the Bavarian Alps, Dr. Alexandre Migala crept up a grassy slope littered with hidden explosives.

Some German children had trespassed onto the military base and were severely injured in a blast. Alexandre, just one year out of TCOM, treaded gingerly around the copper casings of aging 40 mm grenades.

The first Migala brother to attend UNTHSC, Alexandre arrived at the Fort Worth medical school almost by accident. While studying medieval renaissance history at the University of Texas at Arlington he went to a student Biological Society meeting, mostly because he heard there would be free sandwiches.

He signed an attendance form, which found its way to TCOM. Soon he got a letter from the medical school inviting him to visit.

“I figured, ‘Why not?’” Alexandre said. “I went to campus and was immediately blown away by the care and focus the faculty put into helping students succeed.”

He earned a U.S. Army scholarship and did training rotations with military doctors. After graduation in 1993, one of those doctor connected him to an U.S. Army Special Forces unit that needed a new surgeon.

Less than a month after Alexandre joined his unit, he found himself participating in the minefield rescue in the Alps. Afterward, the Chief of Staff for the European Command presented Alexandre a medal.

“The Special Forces guys walked up and said, ‘You’re one of us now.’” Alexandre said. “I had proven I was willing to put my life on the line, and that’s what these guys do every day.”

In Bosnia, Alexandre treated injured international peacekeepers in a clinic set up in a shipping container. In Liberia, he and other medical personnel evacuated or treated 2,173 refugees and American expats while civil war raged outside the U.S. embassy.

Today, Alexandre is Medical Director at the Texas Health Emergency Room in North Richland Hills, and a Colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve as the Command Surgeon for the 84th Training Command.

“I can honestly say I was never afraid to die; only to fail those whom I was sworn to care for,” Alexandre said. “Because during a mission, your world shrinks down to one goal: treating the life right in front you. Otherwise, you are of no use to anyone.”

Disease and danger

Only a lengthy montage could convey Witold’s and Henri’s public health service.

Between them, they have helped the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization and United Nations establish vaccination campaigns to eradicate polio in Madagascar, Haiti, Nepal and Nigeria.

Witold has taken on other infectious disease initiatives, involving cholera, typhoid and guinea worm outbreaks. Henri has joined humanitarian aid activities on food security, water and sanitation, HIV/AIDS, and disaster relief in 18 countries.

Crowded bus rides, exotic foods and occasional dangers fill their storyline.

“I worry mostly about two things when I’m in remote areas of developing countries: children with guns and drug-resistant diseases – especially tuberculosis,” said Henri, now Director of the University of California San Diego International House.

In Nepal, a translator was fixed to Henri’s side, whispering translations in his ear. Soon after, Henri received an email from headquarters saying his translator was coughing up blood and pieces of lung.

Henri tested positive for TB. It took nine months of daily medication to cure him.

Witold served 10 years as chief epidemiologist for the city of Fort Worth. After 9/11, he was appointed Executive Director of the city’s bioterrorism program and led the crafting of the city’s response plan to a bioweapons attack, including developing plans for mass emergency vaccination campaigns.

That expertise came in handy in 2012, when he was part of a CDC/WHO mission to establish polio vaccination coverage in Nigeria. In three months, Witold organized two campaigns that resulted in the vaccination of nearly 3 million children.

Obstacles on these missions abound. Electricity is spotty, roads are rugged and rural areas may have no currency. Earning the trust of locals is notoriously difficult.

“Some of the obstacles are rooted in Western arrogance,” Witold said. “Vaccination teams used to set up clinics without consulting local leaders or health practitioners. The locals, feeling slighted, would start rumors that vaccinations will give the boys AIDS and make girls infertile.

“Now the first thing we do is meet with the village elders and traditional healers. We tell them we have good medicine, but it will only work if we have their medicine too. And, without fail, we garner their support. It’s simply a matter of respect and validation.”

Humanitarian work exposes them to profound poverty and unspeakable tragedy.

In 2004, Henri arrived in Sri Lanka with an emergency response team just four days after an enormous tsunami crashed ashore. Henri was assigned to a village where 1,600 died.

One traumatized father told him that after the first wave, he clung to a rock with his screaming 2-year-old on his back. But a second bigger wave struck and washed the boy away.

“The depth and despair of this man’s emotion was unforgettable,” Henri recalled. “It has been over 10 years and his image, the sound of his hollow voice, are still so crystal clear.”

A lasting impact

Every morning a 90-year-old man wakes up and dresses faithfully in suspenders and a bolo tie. Marian Migala, the family patriarch, lives in a Dallas suburb. Anne died in 2010.

More than a half century ago, Marian brought his family to America, and he is proud his children succeeded. His daughter, Therese Migala Moncrief is a Fort Worth community leader, philanthropist and filmmaker. The fourth son, Arthur Migala, is a college mathematics professor.

During the holidays, Witold surprised Alexandre and Henri with a framed photo of a single brick donated to support renovation of Alumni Plaza at UNTHSC.

Inscribed on it are the brothers’ names and graduation dates, the closing credits to this story about three men who have made a lasting impact on the world.

Social media